Loving It To Death

With more disposable income, more middle class, and the prevalence of information on the internet, travel has seen a boom in recent years like never before. Yet are we in danger of “loving to death” precisely all those places which we’ve long cherished and made famous for enriching our imaginations and bringing our travel dreams to life?

I remember going to China’s stunning Juizhaigou National Park in the mid-1990s. It had just been awarded UNESCO Heritage status then, few travelers had heard about it, and given its remote location in the middle of Szechuan Province, not to mention the horrific roads that had to be traversed to get there (there were no superhighways or bullet trains in China in those days), meant that only the intrepid got to witness its colorful lakes, pine forests, and otherworldly beauty. My partner and I had the place to ourselves, camping where we pleased. There were no rules or regulations, similar to countless other tourist darlings around the planet.

In Machu Picchu in the 90s, you didn’t have to join an organized trip or pay big dollars to secure a place in a queue, not to mention sharing a small campsite with some 500 other folks each night. You just stocked your pack with food, rolled up your tent, and hit the trail. Even in the US, 20 years ago you drove into national parks like Bryce Canyon or Arches, paid your entry fees, and got a tent spot on arrival. These days, if you don’t book online a month in advance, it’s pretty much guaranteed the rangers won’t be letting you in, as the campground has been full for weeks.

How do we manage all the people all wanting to see these magnificent places? In the case of some places, the extreme is just to ban people. The Koh Khai islands off of Phuket did just that in 2016, after 60 speedboats and 4,000 tourists per day visiting from Phuket caused incredible damage to coral reefs and the pristine marine environment. The same was done to Koh Tachai, a gorgeous island in the Andaman that received 1,000 plus visitors per day, when it really only could handle under 100.

Given overpopulation and demand, sorry to say, bans are probably a necessary way to go, although it seems that business and commerce override most of these attempts. Any visit to Trip Advisor will show you that thousands upon thousands are landing on Koh Khai these days, with the place overrun by cafes, bars, and about as far from a paradisiacal tropical escape as possible. You most certainly won’t be citing Robinson Crusoe here.

Some places place semi-quotas or permit systems on tourism to try and preserve sites and culture. Bhutan is the most noted country that does this, not allowing any visitors into the kingdom unless they have pre-booked their visit and paid USD 250 per day for their stay. Unfortunately, visits are not limited to any kind of numbers, but just limited to those with money, which is a kind of elitism that I cannot support. The Bhutanese claim they don’t want their country to become another Nepal (essentially full of hippies and backpackers such as those that came in the 1970s), but having lived in Nepal I can say that this is a crass generalization, and that there are plenty of spots in Nepal, as well as in India’s Sikkim (which basically has the same scenery, culture, religion, and traditions that you find in Bhutan), where one doesn’t have to fork out an extortionate amount of money to have a genuine travel experience.

On Santorini, darling of the Greek islands, they’ve capped cruise ship visitors at 8,000 per day to minimize impact, and the seafront villages comprising Cinque Terre along Italy’s coast have started limiting tourist numbers, selling a finite number of entry tickets for this year’s tourist season. Quotas are one way to try and lessen the environmental footprint, but they also take out the spontaneity of travel, meaning you’ve got to plan months in advance, and even then have no guarantees of getting in.

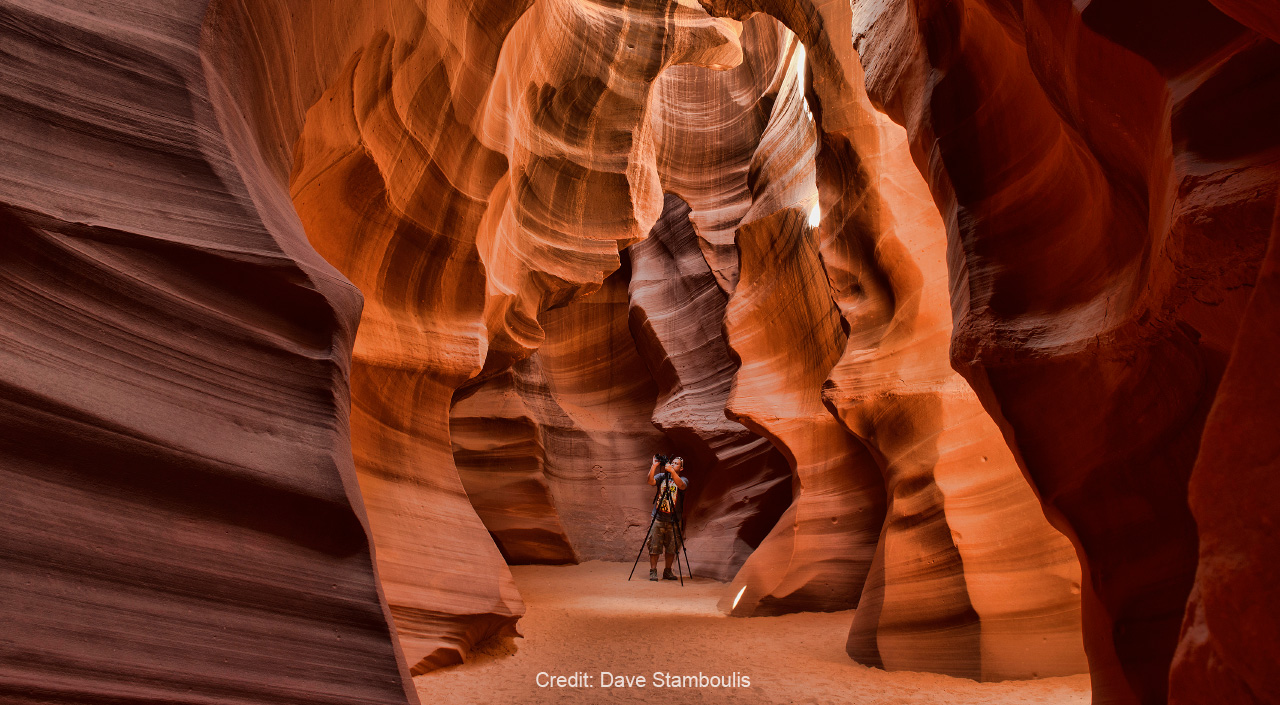

This doesn’t have to be all bad. Several years ago, I saw photos of The Wave, a wildly colorful sandstone maze canyon in northern Arizona. Photographers and hikers have put this dazzling outdoor gem at the top of their bucket lists and rightly so. While 20 years ago you could just walk in (if you knew how to find it), the massive numbers of visitors generated by the internet generation have forced the Grand Staircase National Monument (who administers to The Wave) to create a lottery permit system, with just 10 permits in advance and 10 permits in person given for each day.

The photos I saw were so inspirational I planned out an entire trip to the US just to go to The Wave. I got neither the online permit, nor did my travel partner or I win the lottery on the two days we showed up in person. I could have considered it a major disappointment, but had to look at the plus side. The Wave had been responsible for my entire visit, and because of this, I ended up going to the Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce, and a range of other stunning national parks that I probably would not have visited otherwise.

On a recent visit to Angkor Wat, I became so disgusted with all the tour groups, noise, and crowds that I decided to forego my usual sunrise photo spots and head further afield. I went out to Beng Melea, the jungle temple about an hour or two from Siem Reap that sees a fraction of the number of the Angkor visitors. As opposed to the temple areas at Angkor, Beng Melea still allows visitors to clamber inside the ruins, navigating crumbling building blocks and dense foliage in the jungle. I felt like an Indiana Jones explorer, and had all of my escape fantasies fulfilled.

Undoubtedly, more tourists will come to Beng Melea, rules will follow, and eventually it too will become a tourist trap. There are no easy ways out of the conundrums of mass tourism. We all want to go, we all want to see, and this unfortunately leads to more bans, more permits, and more of everything that is the opposite of an adventure. Perhaps we need to look a little further off the map when planning our travels. Not following the guidebooks, the “top 10” lists, or the crowds. We like to plan and be prepared, and surprise no longer seems to be a major human forte. However as renowned American climber, adventurer, and successful outdoor clothing manufacturer Yves Chouinard says, “Adventure starts when everything else goes wrong.”